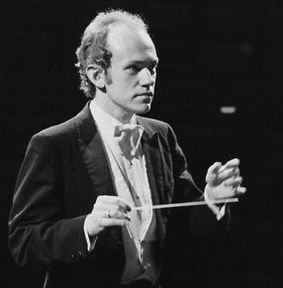

Personal Recollection of Michael Korn (1947-1991), by Janice Bryson Ahead of our celebration of the legacy of Michael Korn on March 23, 2018. Korn, the innovative Philadelphia musician, organ virtuoso and choral conductor, is the founder of the Philadelphia Bach Festival, Philadelphia Singers, as well as the national non-profit association Chorus America. Learn more about him here. We invite you to share your own comments and memories of Michael Korn below in the comments section!

8 Comments

Today, in celebration of St. Valentine’s Day and Choral Arts' 35th Anniversary season, we are shining a spotlight on eight of our members, 4 couples-in-love who sing and play with us. Their devotion to each other and love of music making (be it a professional career or a passionate hobby) is a very special force that contributes to the overall positive and creative environment we all enjoy here at Choral Arts and the Bach Collegium of Philadelphia.

Please meet: Amey Hutchins (Alto) -- Dylan Steinberg (Tenor) Geoffrey Burgess (Baroque Oboe) -- Leon Schelhase (Harpsichord) Patty Cheek (Soprano) -- Ted Cheek (Bass, Board member) Daniela Pierson (Viola) -- Christof Richter (Violin)

Four years ago, on October 16, 2013, Choral Arts and the Bach Festival of Philadelphia, inspired and led by the new bold vision of our artistic director Matthew Glandorf, launched the Bach At Seven series. Introduced on the heels of Choral Arts' big 30th Anniversary season, the idea of the monthly series represented a radical departure from traditional perceptions of what a choir concert format should be.

Although some board members were skeptical about the practicality of such innovation -- because it presented seemingly serious artistic, marketing and attendance challenges -- "the idea's time has come," as David Patrick Stearns wrote in his review for the Philadelphia Inquirer that month.

Choral Arts Philadelphia: a choir rehearsal moment. September 2016. S. Clement's Church. Photo: Sharon Torello. Choral Arts Philadelphia: a choir rehearsal moment. September 2016. S. Clement's Church. Photo: Sharon Torello. Did you know that not all of Bach's surviving cantata scores are easily accessible or usable? This season, Choral Arts ran into a problem finding a few pieces of sheet music when artistic director Matt Glandorf programmed a few surviving “obscure” Bach cantatas to be featured in the “1734-1735: Season in the Life of J.S. Bach” series. In particular, scores for cantatas BWV 207a and BWV215 were not easy to find. The biggest issue, however, was finding a performer-friendly score for BWV 36b Die Freude reget sich (Now gladness doth arise), scheduled to be sung on October 26, 2016. Such score simply did not exist.  By Leon Schelhase For all musicians J.S. Bach and the keyboard are synonymous. Bach’s genius and vision have long stood as a test to every performer in a showcase of sensitivity, knowledge and musical command. The instruments he wrote for were nothing like the modern piano, and although it is common knowledge, we still have few players and audiences that are masters of Bach’s keyboard instruments. The organ aside, the harpsichord and clavichord are only now being regarded as equals to the piano. Of course, when we think of Bach’s keyboard music we are referring to great pieces of music for a solo keyboard instrument. The “Goldbergs”, the “48”, “Brandenburg 5” or the “Partitias” come to mind. However, the keyboard in Bach’s time most typically served the music in a different manner, that of accompaniment.  by Matthew Glandorf In order to talk about the so-called “Historically Informed Performance Practice” movement that began roughly in the second half of the 20th century, we need to go back to the mid 19th century and before. Music, like fashion or film, has been in constant demand, with style and tastes changing quite rapidly. In the Renaissance and early Baroque periods, the notion of performing music that was more than 20 years old was virtually unheard of (with a few notable exceptions). However, with the Romantic era in full swing, it was a performance of the J.S. Bach St. Matthew Passion (March 11, 1829) by the young Felix Mendelssohn that changed the course of public performance.

By Matthew Glandorf The word “cantata” is derived from the Italian word “cantare”, which means a work that is sung. This is in opposition to the word “sonata” (Italian “sonare”), which means a piece that sounds and therefore is instrumental. The tradition of the 17th-century cantata in Italy and France was usually secular in nature and could combine elements of recitative, which is a type of music that follows the contour of recited speech and rhythm, with aria, usually according to a poetic meter. The compositional style of the cantata is mainly taken from the forms encountered in opera. Mythological stories were usually the subject matter such as those of Orpheus, Medea or Hercules. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed